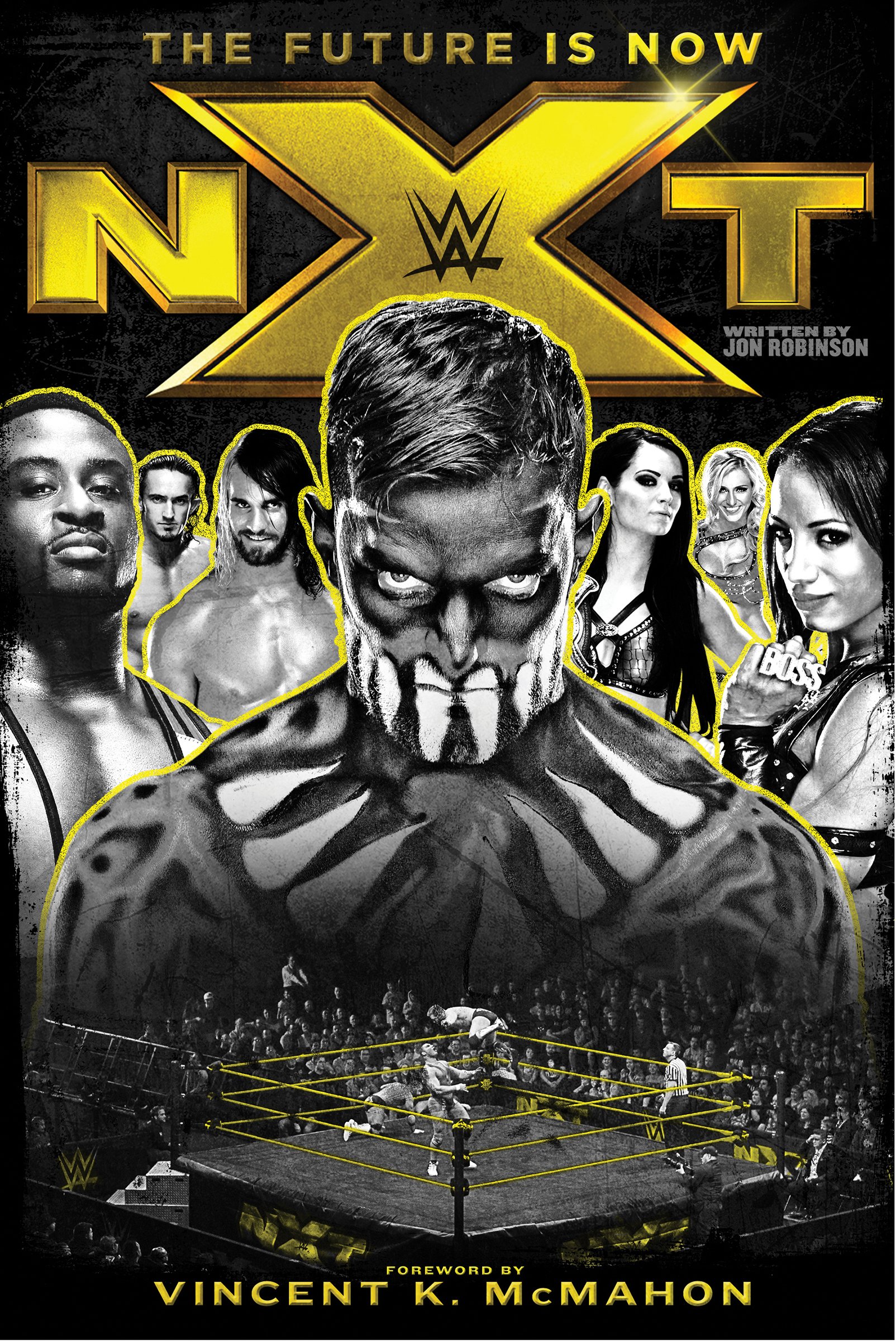

The first comprehensive book on WWE’s hottest brand

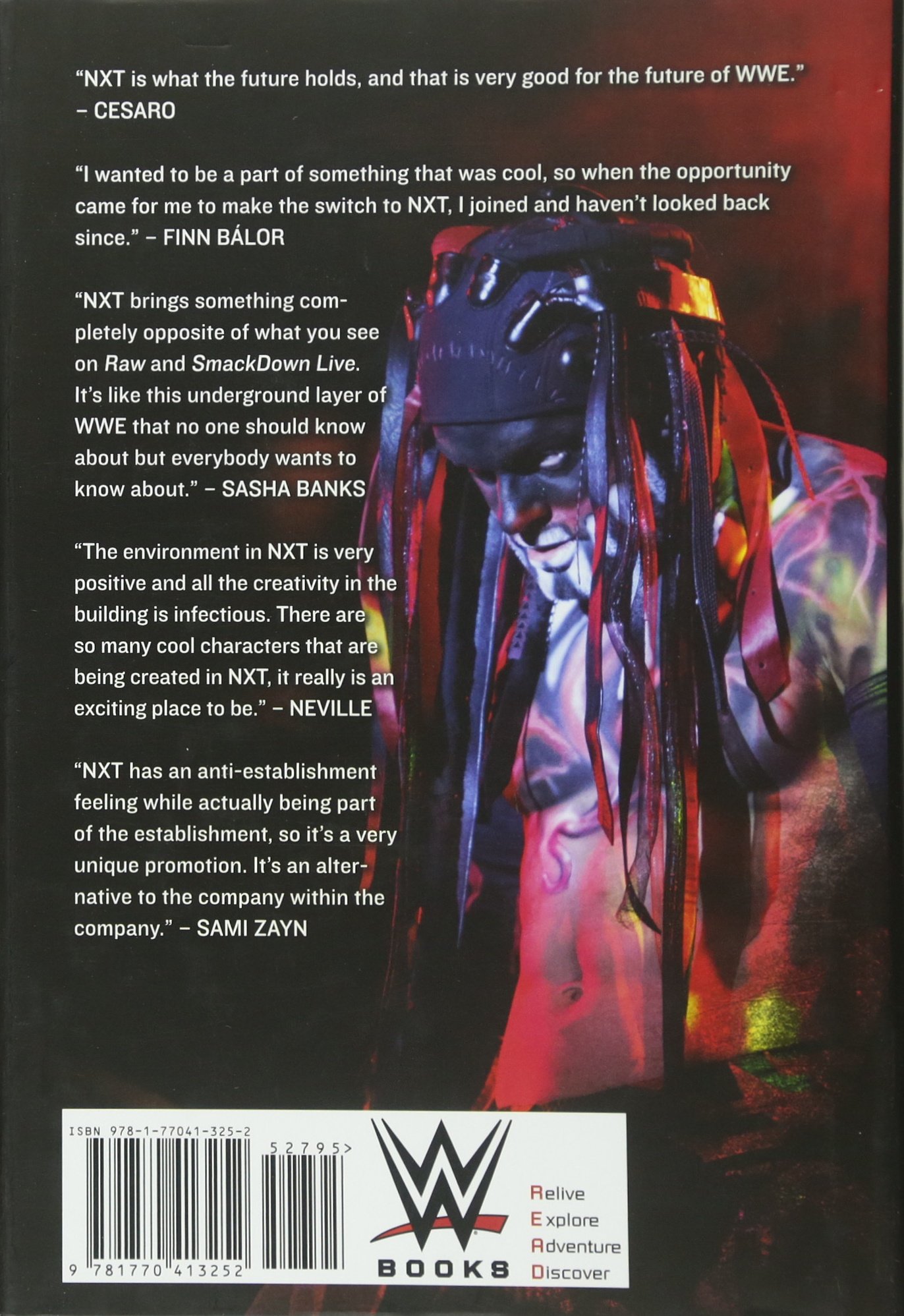

NXT: The Future Is Now follows the rise of WWE’s popular NXT brand from its conception to the brink of taking over WWE with its own rabid following. For decades, sports-entertainment had no centralized system for recruiting and training talent. Recognizing this need, Paul Levesque — better known as 14-time World Champion Triple H — convinced Vince McMahon that WWE must reinvent itself. This book delivers the revealing story of Levesque’s vision and the revolutionary impact it has already had on the WWE landscape, cultivating such world-renowned stars as Seth Rollins, Kevin Owens, Charlotte, Finn Bálor, Sami Zayn, Sasha Banks, and so many more.

Learn about WWE’s groundbreaking approach to talent development and take a look inside the state-of-the-art WWE Performance Center as exciting performers hone their wrestling skills, characters, personalities, and so much more under Triple H’s watchful eye. With new, insightful interviews from Triple H, NXT trainers, Superstars, and other personalities, discover how WWE’s future is now!

Excerpt

CHAPTER 1

Game Changer

“The wrestling business is going to die unless we change our development system.”

Those were the words of Paul “Triple H” Levesque as he sat down with WWE majority owner, chairman, and CEO, Vince McMahon, back in 2010. Triple H’s full-time in-ring career was winding down, and McMahon wanted his son-in-law to begin his transition to office work. To do that, McMahon sent Levesque on a weekend retreat with the head of each department within WWE corporate. Over the course of two days, Levesque heard every last detail of the business outside of the ring, from marketing and public relations to retail and television production.

“The one thing that I thought was strange,” says Levesque, “is that nobody was talking about where the future WWE Superstars would come from. I remember at the end of the meeting, Vince asked for everyone’s takeaways. He wanted to know what we thought about the company and where it was headed. A couple people talked, and then Vince turned to me and asked, ‘So, Paul, what do you think?’ I hesitated at first because I didn’t know I was going to be asked a question, but I said, ‘Hey, I’m looking at all these things we’re doing as a company and they’re huge; they’re awesome. As a performer, I had no idea about all the behind-the-scenes dealings that are going on as a global corporation, but I have yet to hear anybody say anything about what we’re doing to create talent.'” With WCW and ECW out of business, and territories a thing of the past, the days of signing top athletes from rival promotions were long gone, and Levesque feared that the talent pool of future Superstars would eventually disappear.

“Where will the talent come from?” Levesque asked the room of execs. And while he received nods of agreement from those around him, nobody else in the room stepped up to speak out about the issue, and the meeting quickly moved on to other matters. A couple of days later, however, Vince summoned Levesque into his office for a follow-up discussion.

“We need to create a new system,” Levesque told McMahon. “We’re a victim of our own success. We survived every other place closing their doors because you created a brand so successful that’s all anyone will pay to see. But fast forward 20 years. Who are the nobodies today who will be somebodies tomorrow? I don’t see anybody.”

And while Vince was moved by Levesque’s passion, once again, the matter went unresolved. In fact, it wasn’t until 2012, when Levesque started to work full-time in the WWE office, that he was finally given the keys to development.

“When I started working at WWE Headquarters on a full-time basis, Vince told me to talk to everyone in the office and go through everything. He wanted me to find out what I was interested in. He gave me a ton of options for projects to work on, but I just came right back to development,” says Levesque. “I told Vince, ‘I’m back to where I was a couple of years ago. Everything in the company is fascinating, but where are we going to get our talent from? Where is our future headed without new talent?'”

At the time, WWE’s development system was Florida Championship Wrestling, a small promotion run out of Tampa, housed in a tiny warehouse that was anything but big league, with live shows that typically ran in front of less than 20 people, and a television program that was broadcast only on local Florida TV.

“There was a huge disconnect with what we were doing at FCW and what was expected of talent once they made it to Raw,” says Levesque. “How can we expect someone to jump from working in front of a crowd of 40 and two cameras to a show at Madison Square Garden … and it’s on live TV? Where are the cameras? What am I doing?”

“FCW TV didn’t give you a lot to be excited about,” adds Corey Graves, the NXT and Raw announcer who began his WWE training as an in-ring competitor in Tampa. “The matches were fine, but as far as production quality, it aired on some local Florida channel that all of 13 people got, and it just didn’t feel like TV. There was no sense of accomplishment from being on FCW TV; it was just for practice. Back in those days, there was such a disconnect between the main office and FCW that the main roster and the office was like this mythical being. We knew they existed, but they didn’t pay any attention to us. We were kind of this dirty little secret down in Tampa, doing what we wanted to do because no one was paying attention anyway.

“I remember people would come down from the office, whether it be a writer or someone from creative or a producer, and a swarm of guys would crawl over each other just to get a shot at talking to them. All anyone thought about was, ‘Get me out of FCW! Put me on the main roster.’ We just wanted to get on the road. We were tired of that warehouse, and it was like a dogfight to get ahead — to get attention. It wasn’t even necessarily to get out of there, you just wanted to know that what you were doing was being paid attention to. Even if the only feedback you got was, ‘Everything you’re doing is wrong. You suck.’ At least you knew that someone at WWE Headquarters realized you existed.”

Beyond local Florida television, FCW talent were also being introduced to a national audience at the same time, thanks to NXT on SYFY, an experimental reality show that began in 2010. Unfortunately, at that time the show degraded the talent more than it showcased them, as each rookie was paired with a WWE veteran and was often made to look like a fool rather than the future of the business.

“When NXT originated, they said it was a reality show, but it was more like torture,” says Bray Wyatt, who was featured on season two of NXT under the name Husky Harris. “When we were put on the original NXT, I remember William Regal walking up to us and saying, ‘Fellas, I don’t know how you do this. If this was how I started, I never would’ve made it.’ Those weren’t very encouraging words, but that’s how the format was. We were thrust out there; we were nothing; we were embarrassed on a weekly basis, and we were given these horrible names with no creativity and nothing behind them. It kind of ruined us. It ruined all of us for a long time. It was a bad time, especially for me. I never felt like myself.”

“I’m not necessarily sure it was designed to make stars,” says Daniel Bryan. “Now that I saw what took place during the filming of Tough Enough, a show where new talent attempted to earn a contract through a reality TV setting, I realized that the most important part of the experience was to try to create a compelling TV show. That’s why we were doing things like monkey bar climbs and drinking soda on not-quite live but nearly live TV. For someone who doesn’t drink carbonation — it’s like literally a million people watched me struggle to drink soda on live TV.

“I almost feel like being on NXT hurt me. The only positive was that by being paired up with The Miz and by being forced to lose every match, I gained a lot of sympathy, just because they treated me so poorly. I remember when I first went out and lost to Chris Jericho, it was no big deal; it was great for me to be in the ring with a legend like that and to be competitive. Then I lost the next week because of injuries; again, it’s no big deal, it fits with the storyline. But then it became this thing where instead of losing for a good reason — to make me an underdog — it’s like, ‘Nope, he’s just on a losing streak; he loses every match.’ And because it’s a short show — it’s only an hour — and we have all these stupid competitions, I never had time to gain back any momentum. It was like, ‘Hey, he’s losing to these other rookies in two minutes because he’s not very good.’ What helped me was Michael Cole and those other guys burying me on commentary, saying, ‘Oh, look at him, he’s just a nerd.’ And being paired with The Miz, who was legitimately not liked by the WWE Universe. So they were like, ‘Hey, Miz is being mean to this guy, and we don’t like Miz, so we are going to cheer for him even though he loses every match. And we hear these other guys talking about how bad he is, so we are going to cheer for him even more.’ It just didn’t seem like it was a good way to introduce stars.”

Levesque agreed, and in 2012, when he was put in charge of the newly formed part of the company called Talent Development, it was up to him to change the culture.

Vince’s words to Levesque were simple and to the point: “You told me what the problems were in development, now it’s up to you to tell me how to fix it.”

“My first goal was to create a bridge between the office and how we worked with talent,” says Levesque. “That slowly morphed into something where I needed to take over talent relations and I needed to take over all of these other responsibilities in order to get it right.”

Levesque headed to Tampa to take a closer look at what was really going on in FCW, and, more importantly, to figure out how to fix it. FCW live shows at the time were averaging 15 fans per date; there was more talent in the building than actual paying customers.

“When I was in FCW, it was very different. It was very much like an island unto its own,” says Tyler Breeze, who began his WWE training under the name Mike Dalton in FCW. “Every now and then, they would have a showcase where Triple H or Undertaker or one of the writers would come down, and they would get to see everybody who was in FCW and what they were all about. It would give them a peek at who was down there. But that was only once every couple of months, maybe, so they didn’t really keep up with the program, and it definitely wasn’t a day-to-day type of thing.”

Seth Rollins also saw the FCW process as extremely frustrating. “The brass didn’t have eyes on us at all times. I think there was one guy in the office in Connecticut who was watching our tapes, and if he could get through to the brass in Connecticut, maybe we’d get a shot,” says Rollins. “Otherwise, it was just what they needed at the time. Maybe they needed a Spanish-speaking guy; boink, let’s pull him out. It’s not like they were building prospects down in FCW. You just had to bite your tongue and deal with the taste of blood. It was a very difficult struggle for me, sitting there thinking I had so much to contribute and not being able to showcase that on a regular basis. The only way to temper that frustration is to dive into what you’re doing.”

Beyond fighting for the attention of the main office, another problem with FCW was the facility itself. A dingy warehouse with three rings and no gym, talent would arrive in the morning to work out in the ring, leave to lift weights at a local gym and eat, then return later in the day if they had a promo class to work on their mic skills with WWE Hall of Famer Dusty Rhodes.

“When I got to FCW, it was very different,” explains Baron Corbin, who retired from the NFL to give his dream of sports entertainment a shot. “In FCW, we had street teams who postered towns with the shows. I was humbled greatly when I was given a sign and told to stand on the corner in town for hours, telling people to come to that night’s show. ‘Come to FCW, where you’ll see the future stars of WWE.’ Coming from the NFL, I was used to being treated well, and I came from an environment where everything was taken care of. When you’re in the NFL, everybody bends over backwards for you; then you come here and you’re standing on a street corner with a sign. It was really good for me. It was a humbling experience. In that locker room, all you had was a bathroom to change in and chairs along the wall. It was a grind. By no means was FCW easy.”

Levesque talked to the talent and coaching staff of FCW, dug down deep into their development process, and walked away unimpressed. Even worse, he found the facility uninspired. While the coaching staff taught students wrestling basics, there was nothing at FCW that felt “next level” to Levesque, and the old-school training techniques of slamming bodies on mats to prove toughness just didn’t jive with what modern athletes needed to transform into Superstars. And since FCW live events often featured more wrestlers than fans, students who were called up from development frequently found themselves overwhelmed at the differences between gym practice and Raw reality.

“I traveled down to Florida to visit FCW and see what they were doing, but they really weren’t doing anything special. Then it was up to me to figure out how to change the process that talent went through so they could sign and train and be ready to step up and join the main roster,” says Levesque. “We needed to create a system to design WWE Superstars. Knowing everything that I knew about being a WWE Superstar and knowing what I did in order to get there, I wanted to design a process that would help signed talent become Superstars who could carry the brand for the next decade.

“I thought, ‘If I was a young kid who wanted to be a WWE Superstar, what would I need to do? How could I get there?’ To me, it came down to a couple of things: we needed a first-class facility to attract the top talent from across the world. There are millions of people out there who are like, ‘I’d love to become a WWE Superstar,’ but that’s like saying, ‘I want to be a trapeze artist.’ How do you even go about getting started? And how do you find the millions of people who want to do this? How do you attract them? It’s one thing to say you want to do this; it’s another thing to say, that you want to go to some dumpy warehouse in Florida with an audience of five people. How do you create a facility to attract them? How do you go about creating and giving talent a platform to do what they do best?

“When I went to WCW back in 1994, I didn’t know anything about television. I learned it on the fly because I knew I needed to know it and nobody was teaching it to me. I just talked to everybody who was there and I learned what they did and how they did it and why it mattered. When I got to WWE, I had some knowledge of how television worked. If I didn’t have that knowledge, there’s no way I would’ve made it. So to me, new talent needs a smaller platform, so we can explain, ‘Here’s how you do it.’ That way, when they get to the bigger platform and we tell them, ‘Look at the hard camera,’ they know what we’re talking about. If you take a step beyond just the performers in the ring, I also realized that there needed to be a change on every level. We had cameramen and technicians and directors and producers and all these people that, while they are great at what they do, they’ve been doing this for us for quite a while and are getting older. What if they decide they don’t want to do this anymore? What do we do?

“We had to start over from square one and teach people on every level how we do what we do. And that was cameramen, technicians, ring announcers, commentators, play-by-play, all of it. I realized right then and there that we needed to change the game. We needed a new way to develop talent on all levels. The process started then.”

About the Author

Jon Robinson

Jon Robinson is an award-winning author and journalist whose work has appeared across media including ESPN, Sports Illustrated, GamePro, and IGN.com. He has written eight books, including Rumble Road, The Attitude Era, NXT: The Future is Now, and Creating the Mania. His book, The Ultimate Warrior: A Life Lived Forever won the IBPA Benjamin Franklin Award for Best Biography.